Thanksgiving is always a busy time for our family. November 21 is our anniversary (34 years!), and Thanksgiving follows closely behind. This year, Kimberly and I had a one-night stay at a luxury hotel and a wonderful dinner and breakfast in the first part of the week. Then, after a Thanksgiving meal with another family, we headed off to the Smoky Mountains with our kids for a very cold and beautiful time outside of Highlands, North Carolina.

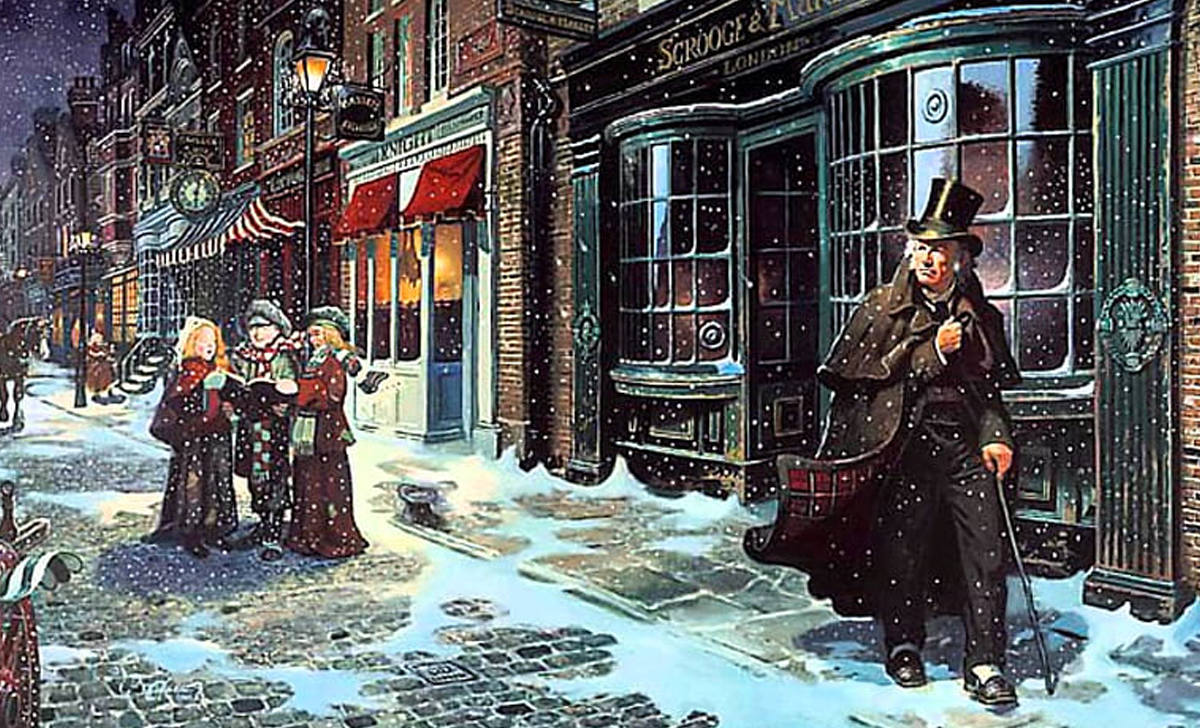

Saturday night, after dinner in town and a failed attempt to endure a freezing cold Christmas tree lighting, we settled in for an evening of Christmas movies. One of the movies we watched was Patrick Stewart’s version of A Christmas Carol, written by Charles Dickens. This short story has been adapted countless times for stage and screen. When I was in high school, I even had a bit part in a musical version. It's a Christmas staple. Most people in our culture are familiar with the story, so much so that it's added to our language the word “scrooge” as a miserly, unpleasant person.

What is not generally known is Dickens' contribution to Christmas as we understand it today. In Dickens' time, Christmas was not centered on children, family, or helping the poor. It also wasn't about worship and Christ. In fact, many churches were locked up tight on Christmas Eve because it was dangerous to go out. Christmas was a time for drunkenness and carousing. Working classes would get drunk and go door to door through wealthy neighborhoods demanding food and drink under threat of violence and property damage. A memory of those times is found in the Christmas song, “We Wish You a Merry Christmas,” with the demand for figgy pudding and the veiled threat: “We won't leave until we get some, so bring it right here!”

Dickens was one of several people, and probably the most important one, who cast a new vision for Christmas as a celebration of Christ that focused on family togetherness, the needs of children, and mercy for the poor. Dickens was not a theologian, and his theology was not great (he wrote a book about Christ), but he certainly had a heart for the things Christ has a heart for. He pounded the drum for these concerns in most of his stories. And in some ways, “A Christmas Carol” was the least subtle of his messages.

In the story, Ebeneezer Scrooge is a man who is committed to hard work and who expects hard work from his employee, Bob Cratchit. He gives Bob Christmas off with pay but resents it. He doesn't have any desire to spend time with his nephew, Fred, on Christmas. There is no indication that Scrooge is guilty of anything other than workaholism, not being charitable, and being ill-tempered. He certainly doesn't actively mistreat anyone. In fact, you could make an argument that Scrooge is a good man. He works hard and contributes to society by paying his employee and not cheating people. But Scrooge is shown that Tiny Tim, Bob Cratchit's sweet boy, will die; and it will be Scrooge's fault, not because of anything Scrooge did, but because of what he didn't do.

What Dickens understood, and then issued as a condemnation to society as a whole, was that God's righteousness is not simply a negative righteousness, where God condemns us for the bad things that we do to one another. To be a righteous (good) person, one cannot simply avoid doing evil. It is not enough simply to hate evil, but we must love what is good. The heart of Christ-likeness is love for others and concern for those who are weakest and most in need: widows, children, and the poor (Matthew 19.14; Matthew 25.40; James 1.27).

God's righteousness is not simply a call to quit doing bad things; God's righteousness is a saving righteousness. God came in the person of Jesus to rescue us from our sin and death, not just to tell us to quit sinning. Scrooge had every worldly thing he needed, but he was spiritually bankrupt and miserable. In Dickens’ allegory, God comes to rescue him through ghostly messengers. Being rescued, he then finds deep joy in showing mercy to others. May we do the same.

Travis Hutchinson, Interim Youth Pastor